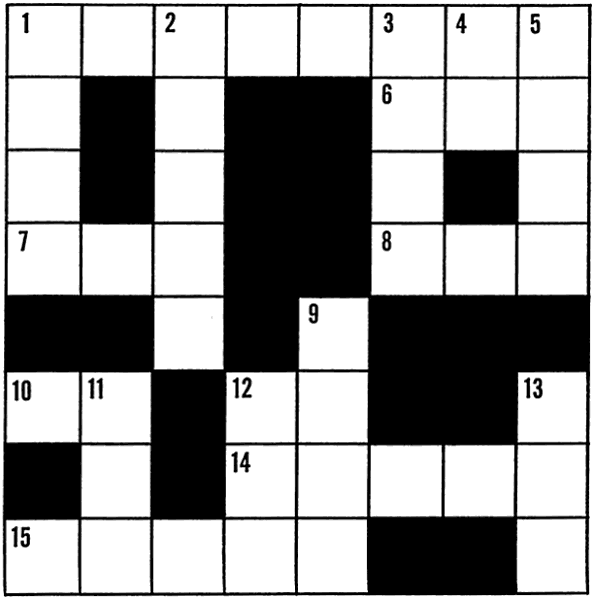

When he plotted out a “Wordplay”-themed crossword onscreen, using grid paper and pencil, I internalized the puzzle’s protocols: perfect one-hundred-and-eighty-degree symmetry, elegantly interlocking words, a minimum of black squares, no jargon or linguistic waste, only “good words.”

#Clipt art of woman doing crossword puzzle code#

But with his simple puns he seemed to be accessing something foundational about language-a code that could be rearranged and manipulated through sheer brainpower. The hard-core kitsch aesthetics of Reagle’s life were not exactly what drew me in.

#Clipt art of woman doing crossword puzzle full#

That’s ‘No, a Shark’ !” His house is full of crossword paraphernalia: black-and-white ties, mugs, and a crossword mural in his living room. Later, when coming across the phrase “Noah’s Ark”: “Switch the ‘S’ and the ‘H’ around. “Dunkin’ Donuts-put the ‘D’ at the end, you get ‘Unkind Donuts,’ which I’ve had a few of in my day,” he says. Reagle’s cameo is distinctly unglamorous: we see him in a midsize sedan, driving by Florida’s strip malls, riffing on the roadside signage.

Most of what I knew about crossword construction came from the 2006 documentary “Wordplay,” in which Merl Reagle, the late syndicated puzzle-maker, walks the viewer through the mechanics of designing a crossword. My first crossword puzzles reflected my high-school preoccupations: an early grid was “midterms”-themed, featuring words with “term” in their middle: DETERMINED, MASTERMIND, WATERMELON. I filled notebooks with calorie counts and clues, meal plans and puzzle themes. As I tried harder to escape the trappings of my body-to become a boundless mind-I plunged deeper into a material world of doctors, therapists, scales, and blood samples. A little obsessive, maybe-but the cultural residue of female hysteria, a century later, might have you convinced that this simply meant “adorable.” And, without a doubt, she must be smart. She must be disciplined, I imagined people thinking. “Crossword-puzzle constructor,” I found, was an uncannily compatible identity-container. Diagnoses for mental illness are notoriously reductive, and I wanted to be reduced. It was a distorted fantasy of success that ignored the actual demographic reach of eating disorders and betrayed the stony limits of my teen-aged imagination. I found in the common identifiers of the disease-extreme thinness, perfectionism, a penchant for self-punishment-a rigid template on which to trace my pubescent identity. I read in a health-class textbook that high-achieving, affluent young white women were the population most likely to succumb to anorexia.

The connection between these impulses felt intuitive: they both stemmed from a desire to control my image and to nurture a fledgling sense of self. I began writing crosswords when I was fourteen, which is also when I began starving myself. It was this paradox-the promise of control and transcendence-which first drew me to the prototypically modern grid: the crossword puzzle. “The grid’s mythic power is that it makes us able to think we are dealing with materialism (or sometimes science, or logic) while at the same time it provides us with a release into belief (or illusion or fiction),” Krauss wrote. In 1979, the art critic and historian Rosalind Krauss wrote about the ubiquity of the grid in modern art, citing the even-panelled windowpanes of Caspar David Friedrich and the abstract paintings of Agnes Martin. From sidewalks to spreadsheets to after-hours skyscrapers projecting geometric light against a night sky, the grid creates both order and expanse. A grid has a matter-of-fact magic, as mundane as it is marvellous.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)